*This essay features photography of Bukit Brown by Brian McDairmant

Before they were made to rest in their graves, those now lying in Bukit Brown Cemetery might have imagined a celestial gaze beaming down upon them. Ornate designs on the tombs remind of Chinese beliefs and customs. Epigraphs carve incredible stories from Singapore's pioneer generation.

Today, that gaze belongs to Google Earth. In a country whose cartography reads like a network of capillaries, Bukit Brown Cemetery is an insolent, self-contained artery, served by a single road after having been closed in 1973. Set in a rare "green lung" in one of the world's densest cities, Singapore's oldest cemetery reserves one of the last live banks of its cultural history. 233ha of lush primary forest house 100,000 graves, some of which dating back to Confucian times.

Exhumation of Graves at Bukit Brown

A screen grab of Bukit Brown according to Google Earth. It is set in one of the last primary forests of Singapore

Redevelopment de rigueur for Bukit Brown

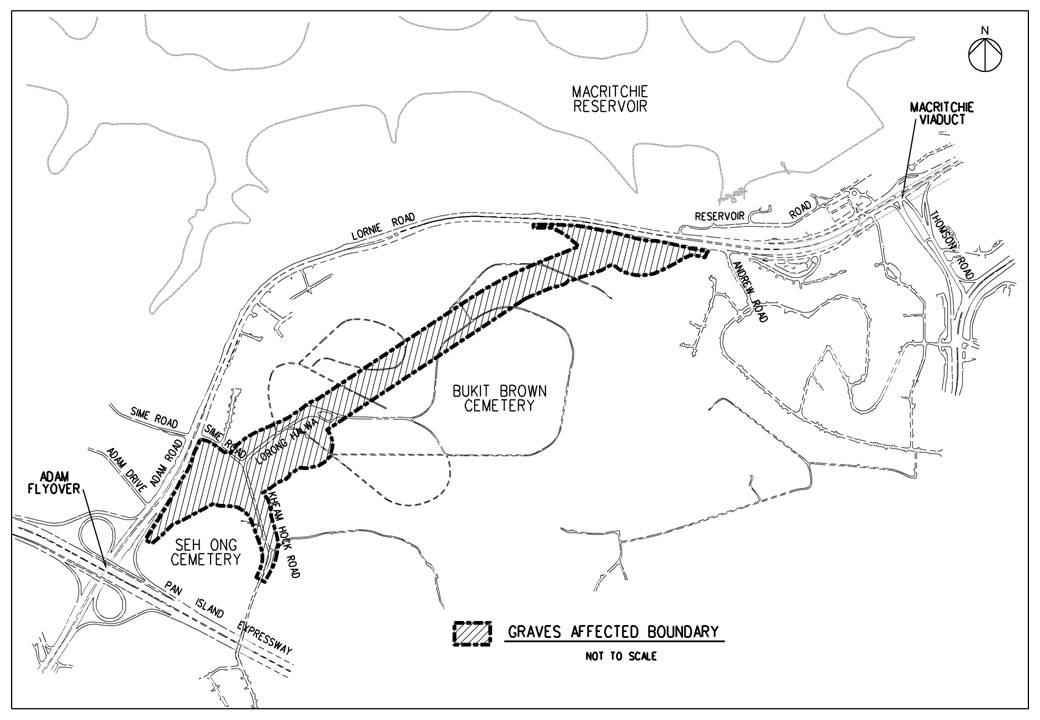

In 2011, the Land Transport Announcement announced plans for an eight-lane highway through Bukit Brown. This marked a surgical incursion through the heart of the Cemetery, wielded by the promise of prime estate. It is slated for private and public housing, as the city-state projects further population growth.

Redevelopment for Bukit Brown was new in neither plan nor principle. It was actually first announced in 1991. There was little fanfare then. It was a cemetery, an "inauspicious" space, and a singularly Chinese one-outliers in a cosmopolitan boomtown. The city-state had, in five decades since independence, quickly cultivated a no-nonsense reputation for itself as a powerhouse nation-building on practical economic principles. Indeed, it was that hard-nosed pragmatism that saw Singapore become a global curio of admiration.

But the protests swelled. Within a year, multiple civic groups were spawned and news reached the international media. From obscurity, the Cemetery suddenly found itself buoying the surface of discussions around heritage and habitat, an almost mystical sight amidst the city's unbroken flotsam of roofs and skyscrapers.

Heritage, habitat, and cultural "habitage"

For a time in the 1960s, it seemed Michel Foucault would be proven right about our fear of cemeteries in his essay on heterotopias. In Singapore's Master Plan of 1965 and a subsequent announcement in 1972, burial grounds were determined as spaces for urban redevelopment. The seventies saw 273 graves with nary a whimper. Subsequent burials were done away from the city. In comparison, the plight of the Cemetery today is a gate-rattling conjunction of art and activism seeking to forge new modes of visibility.

For example, "The Bukit Brown Index" (2014) is a collaborative project that scissors though decades of foliage which have crept over the memory of the Cemetery in recent years. Cutting against the grain of the cartographer's gaze, the artists speak to the density of the archive instead [i]. One work in the project attends the mammoth-sized task of documenting the names of thousands to be exhumed through the help of artists and volunteers. But of course, this gesture of the archive is always ambivalent: it must coincide with the threat of disappearance itself. This melancholy speaks to the Cemetery's history as a World War II battleground once, when it functioned as grave site for casualties, including victims of the Japanese occupation (1942-1945).

Post-Museum: The Bukit Brown Index (2014)

Many were, and still are, prominent names. Some were Southeast Asian supporters of China's 1911 Republican Revolution. The tombs, mainly Hokkien and Teochew designs, also reflect the unique crosslinks of local Peranakan and European features during colonial Singapore. Some of the deceased peer from photographs imprinted onto curved ceramic-cutting edge technology of their time. This was not seen in neighbouring countries during the same period and is a testament to the prosperity and opportunities thriving in Singapore during the time. These native dialects and cultural influences have largely withered away, through a battery of redevelopment plans and campaigns. At Bukit Brown, however, multiple threads in the nation's tumultuous early years converge, building a dense physical repository for cultural and historical meanings.

The Cemetery therefore represents the rich identities of Singapore today through its provincial origins and vital turning points locally and regionally. The Cemetery's very name, for instance, is KopiB SuaB (g>ge11) -a Hokkien dialect uniquely swigged in Singapore (other Hokkien-speaking territories use a different transliteration of "coffee").[ii] It is this identity placeholder that the documentary "Bukit BrownVoices" chronicles during Qing Ming. Every year, the tomb-sweeping festival gathers families to remember their ancestors. It is a stalwart on the local Chinese calendar[iii], and a period during which The rich material culture become potent touchstones for practices and rituals come alive entwined with stories of the past and reflections upon the present. And families have nevertheless pre-empted exhumation, eager to perform the appropriate rites before the bulldozers come.

What politicos and the general public thought were dead ground was revealed to be a live generator and re-generator of a kind of "habitage" as people discover and re-discover meanings of self and group amongst rituals and behaviour. It is to that deep heritage value that a.t. Bukit Brown, a civic group, dedicates itself to documenting, preserving, and educating. The Brownies (as they call themselves) provide voluntary tours of Bukit Brown, every Saturday and Sunday, rain or shine.

The Nature Society Singapore found within Bukit Brown 90 resident and migrant bird species, almost one quarter of Singapore's bird species. Thirteen are nationally threatened, such as the red jungle fowl and the white-bellied woodpecker. It has 48 forest species, almost half of Singapore's total, in such a small area, "highly impressive for a woodland area like Bukit Brown".[iv]

Dropping the word "cemetery" is therefore a conscious effort at expanding the conversation beyond the dead. The cemetery is not a dead site, but a potent site of regeneration and inhabitation for humans and animals. In other words, the "dead" as a category is not devoid of its own political and cultural agency, evident in these examples.

Cumulatively, these efforts have helped place Bukit Brown on the 2014 World Monuments Watch (WMW), an international list of cultural heritage sites which are being threatened by nature or development. There is hope that this listing could help with conservation efforts, no less from a neighbour; the historic enclave of Georgetown in Penang, Malaysia became a UNESCO World Heritage Site after being listed. Of the coup, Claire Leow, one of the organisers of All Things Bukit Brown, has said: "I hope it motivates communities to do more to take ownership."

A child's grave at Bukit Brown. Photo credit in this series: Brian McDairmant.

A child's grave at Bukit Brown. Photo credit in this series: Brian McDairmant.

Rituals during Qing Ming, the festival of the dead, led by a Taoist priest

Rituals during Qing Ming, the festival of the dead, led by a Taoist priest

Filming for the documentary Bukit Brown Voices, as a descendent carries out Qing Ming rites

Filming for the documentary Bukit Brown Voices, as a descendent carries out Qing Ming rites

These uniformed Indian guards were Indian men who arrived from Northern India as peace-keeping forces in the late 1800s. In the early 1900s, many of these men were enlisted into the local police force, and many worked as guards for the property of private wealthy individuals

Sikh guards are a unique part of Singapore history. Families erect sculptures of Sikh Guards beside their ancestor's gravesite in the hope that the Indian guards would continue to guard and protect their ancestor's resting spot.

Sikh guards are a unique part of Singapore history. Families erect sculptures of Sikh Guards beside their ancestor's gravesite in the hope that the Indian guards would continue to guard and protect their ancestor's resting spot.

A view at Bukit Brown through the lush greenery

A view at Bukit Brown through the lush greenery

Locating The In/Visibility Divide

The fact is the dead have never been invisible. From the country's colonial days through to its post-Independence reforms, the Cemetery has been the site of complex political exchanges. Calls within post-colonial Singapore to sanitise and reallocate land reveal sites like Bukit Brown to be significant variables in urban policy. From the eye of the urban planner, the rumblings of the dead a hundred feet below are impossible to hear.

In Bukit Brown, however, the dead signify a pre-history of peripheral communities including clan-based organisations, casually employed grave-diggers and wildlife varieties whose political visibilities are slowly being eroded, like soil, by the tractors of today's policies.

In this case, the dead are urban creatures. "Ghost" stories become key interlocutors of the experience of urbanisation. In Jean Tay's 2004 play Boom, a talking corpse comments profoundly on the loss of memory amidst a scenography of urban restructuring.[v] In others, stories of visits to the Cemetery reveal a curiosity for an urban environment beyond its skyscrapers and forward projections:

The birds and the squirrels have seemed to make Bukit Brown their haven and heaven. The birds seemed to be enjoying their games of flight about the forested area of Bukit Brown while the squirrels looked as if they were safe in their hideouts...amp; Do the animals know the eventual fate of Bukit Brown? Maybe they had by their sheer nature, trusted us human beings to look out for them? [vi]

Politicians, too, understand the fragility of identity in the abstract of time and space. In Singapore's National Day Rally Speech in 2011, the Prime Minister asserted the necessity for anchors to the past:

"We are Singaporeans together on a small island. We are anchored by our emotional links with family and friends and by our shared sense of our history and our common destiny. We are not just here, materialised out of nowhere...amp; We came here somewhere, sometime there was a history to it and it is crucial to remember where we came from, how we got here."[vii]

But as the "The Bukit Brown Index" reminds, in a huge printout of the Land Acquisition Act laid on the floor amidst its other works, regenerative interest in social-cultural meanings of home and identity is often politicised. This is especially important in urban contexts where fast growth and change have created a "cultural amnesia". Urban citizenry search for a pause button to order their inherently malleable environment, and often that lies in political leadership.

Seen in this light, the art surrounding Bukit Brown is both a making visible of the past as well as its reconstitution within today's political realities. In Boo Junfeng's two-channel video installation "Mirror" (2014), the Cemetery becomes a site for one such reworking; two soldiers (played by the same actor) encounter each other in the Cemetery in spite of their apparent historical differences.[viii] Incongruously placed, the characters enact a mise en abyme that suggests an overlapping of the past with the present. To reject the Cemetery as an irrecoverable artefact may finally uncover the key to its political relevance today. Looking into the "Mirror" then, we find that the past of Bukit Brown becomes strategically reworked around narratives of nation-building, military service and ethnicity that are more pertinent in today's politics than they ever were before.

Much of the controversy on Bukit Brown have hinged on the point that there was no consultation with the public prior to the decision. The official standpoint is that this is an intractable problem. Stephen M. Gardinerbs bmoral stormb could describe this predicament.[ix] His arguments about climate change could be applied to instances such as Bukit Brown. What are the responsibilities of the current generation, especially those in developed and rapidly developing nations, regarding the wellbeing of future especially when there are considerations yet unseen?

Straitjacketed by considerations economic, technological and political, there seems little in the hierarchy for morality. However, the groundswell of support and attention to sites such as Bukit Brown becomes an important moral rebalance in the turbulence of urban redevelopment.

NASRI SHAH is a forthcoming MA candidate in modern and contemporary art at the Courtauld Institute. He graduated with a degree in History of Art from UCL, where he was a recipient of the Rudolf Wittkower Prize. His research interests at the moment include intersections between art and geography, as well as queer theory.

MELANIE CHUA is an editor and writer. She has edited and written on socio-cultural issues and the arts for magazines, books and case studies. Her own work holds a humanistic interest in urbanity and contexts as well as an experiment with form.

ii http://thebukitbrownexperience.wordpress.com/developmentplans/viewspoint-shs/

iv Nature Society (Singapore)'s Position on Bukit Brown (position paper), http://www.nss.org.sg/documents/Nature%20Society's%20Position%20on%20Bukit%20Brown.pdf

vii Prime Minister Lee's National Day Rally 2011 (Speech in English), 14 Aug 2011.

viii Boo Junfeng, Mirror (2012), http://boojunfeng.com/2013/01/25/mirror-2013/

ix Stephen M. Gardiner (2013). A Perfect Moral Storm: The Ethical Tragedy of Climate Change (Environmental Ethics & Science Policy).